The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana

by Jess Nevins

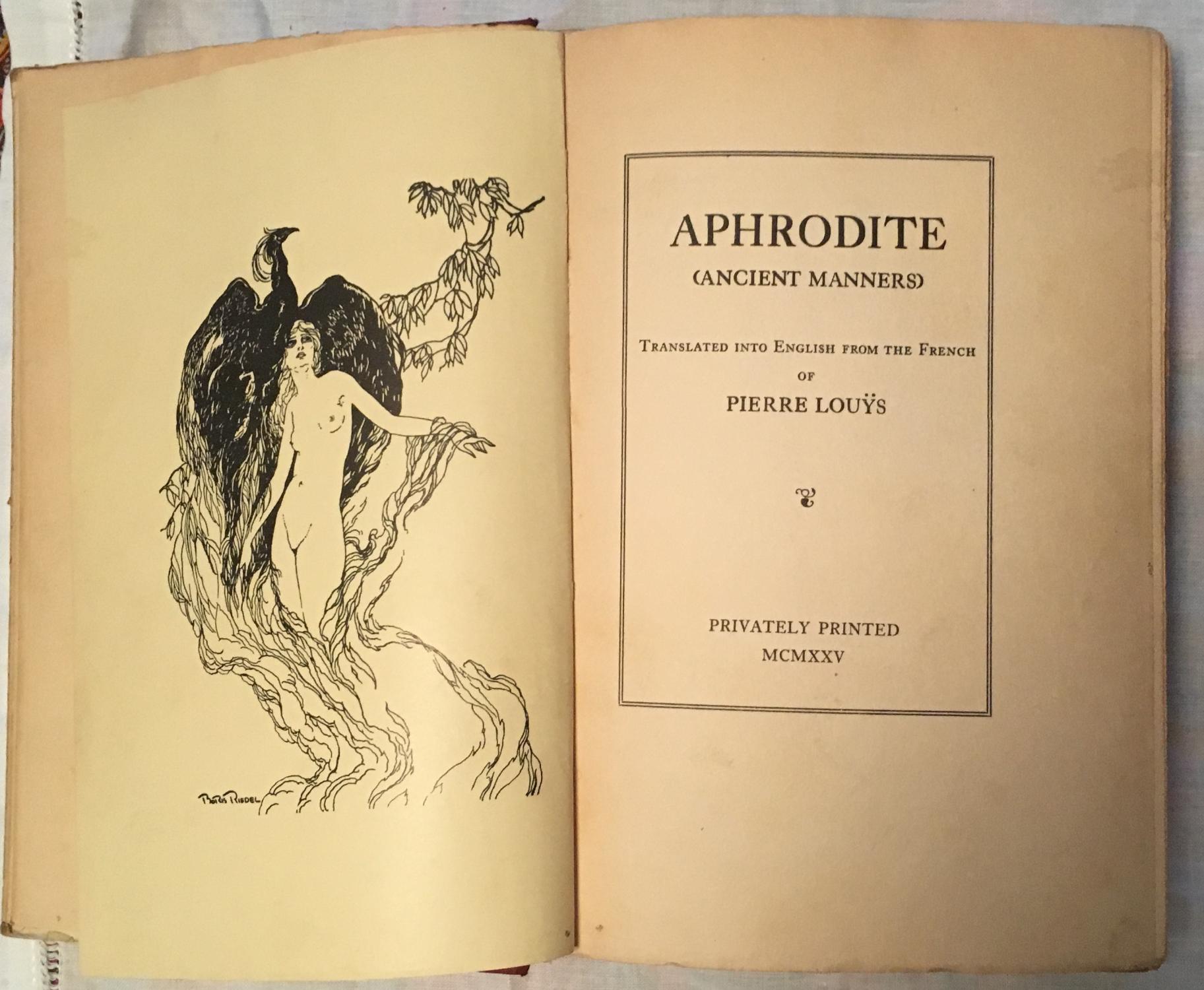

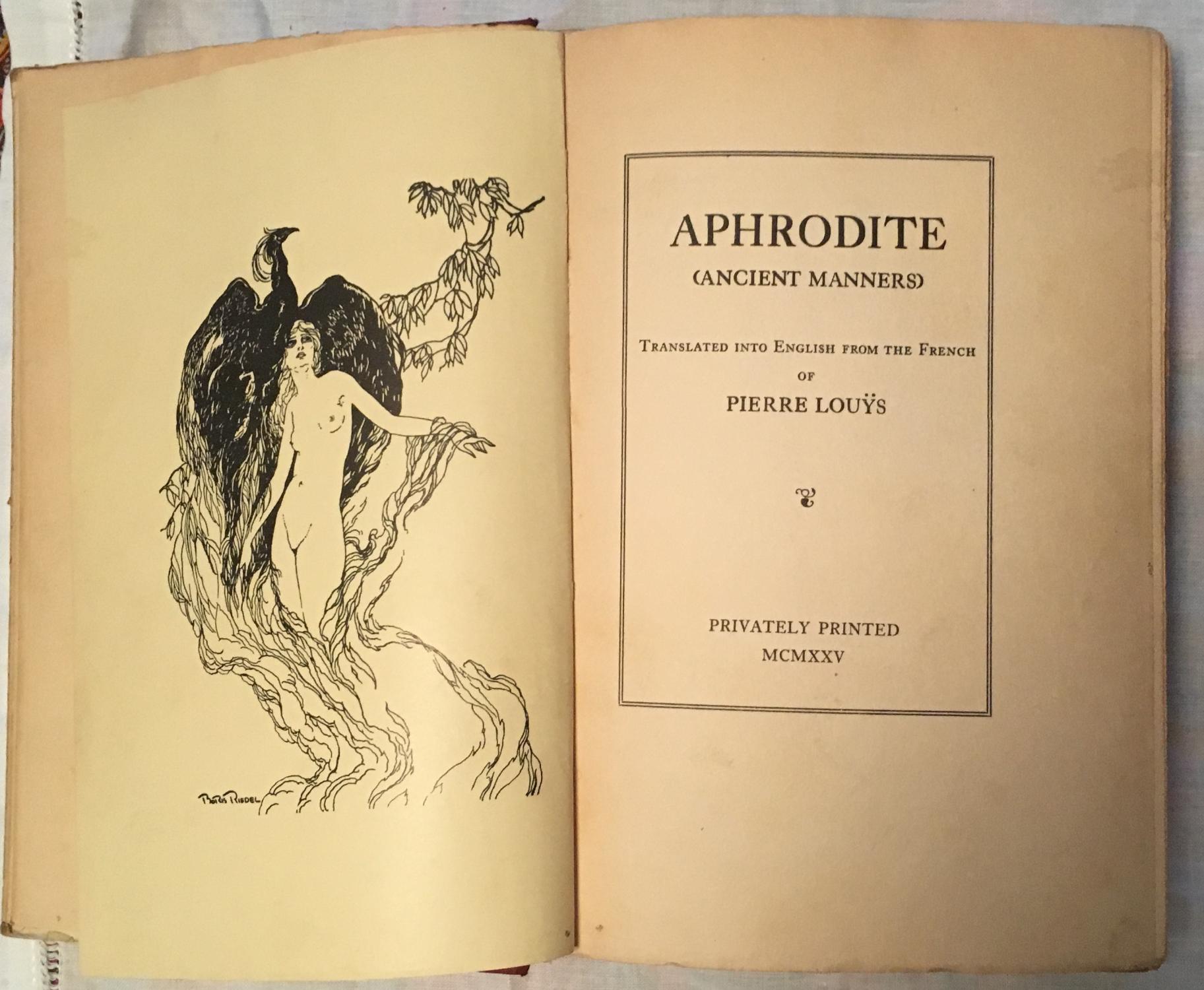

Aphrodite: Ancient Manners (1895)

copyright © Jess Nevins 2022

Aphrodite: Ancient Manners (original: Aphrodite: Mours Antiques) was written by Pierre Louÿs. Louÿs (1870-1925) was a minor Decadent French writer connected with Mallarmé, Gide, Valéry, and Debussy. He wrote a number works of erotica which argued for a classical view of morality rather than a modern Christian view. He is best remembered for Aphrodite, whose notoriety has lasted even to the twenty-first century. The novel is eye-opening, a memorable piece of exotic and erotic Romanticism: a sort of lesser Salammbô, but with lots of sex.

Aphrodite is about Chrysis, the most beautiful and desired courtesan of Alexandria. She has had many lovers/customers/patrons, but none have touched her emotionally, and she feels a certain contempt for the men who fall in love with her. But one day she meets Demetrious, the exquisitely handsome sculptor and lover of the Queen. Demetrious has tired of the Queen, and despite all the women of Alexandria lusting after him, he does not involve himself with any of them. But when he meets Chrysis he falls in love with her, and asks her to go home with him. She refuses him, on the grounds that she’ll be just another conquest to him. She asks him to prove himself to her by bringing her three gifts: a silver mirror owned by a rival courtesan; an ivory comb owned by the wife of the High Priest, who Chrysis dislikes; and the necklace of pearls hanging around the neck of the statue of Aphrodite in the Temple of Aphrodite Astarte. Demetrious objects to this, and to take his mind off of Chrysis visits the Temple and has sex with one of the temple prostitutes, an eleven-year-old, but he is taken with Chrysis, and the sex with the eleven-year-old does not sate his desire for Chrysis. So Demetrious steals the mirror, kills the wife of the High Priest (who gives herself to Demetrious willingly, so strongly does she lust after him), and then steals the necklace of pearls from the statue. The theft of the mirror is discovered, causing an orgy to turn ugly and the slave who was due to be freed during the orgy to be crucified. The body of the wife of the High Priest is discovered, and soon after that the theft of the necklace of pearls is discovered, and the prostitutes of the city become frightened that the gods will forsake them. Meanwhile Demetrious has a dream in which he and Chrysis have perfect, joyous sex. When Chrysis and Demetrious meet up again he gives her the three objects she asked for and she avows her complete love for him, the first real love she has felt for a man, but he coldly spurns her, telling her that after the dream he had, the reality would be unsatisfying. She begs him to take her, and he tells her that if she wears all three objects in front of the crowd of prostitutes, he will see her again. She does so and is condemned to death by drinking hemlock. He sees her again but is unkind to her, and so she gladly dies and is buried by her friends.

Aphrodite is sui generis. Louÿs wrote it as a rebuke of Christian sexual morality and a proclamation of the superiority of the sexual mores of the ancients, both the Greeks and the Egyptians. But rather than simply writing pornography, Louÿs wrote his paean to sex in the form of a historical romance. So the novel lacks the explicitness and the ugly morality of de Sade’s Justine (1791), and is considerably spicier than Salammbô. But Louÿs does take some of the same approach to his subject matter as Flaubert, so there is a similar amount of well-researched and accurate historical detail and the same savage, romantic portrayal of the ancients, written in the same lush, sensual style. Aphrodite is a sensual novel in terms of the sex but also in terms of the appeal Louÿs’ descriptions make to the senses. The characterization is solid and the dialogue entertaining and occasionally witty.

The main theme of Aphrodite is carnality, and although the Alexandria of the novel can be described as “decadent” that term has certain pejorative overtones with which Louÿs would undoubtedly disagree. He approved of the world he portrayed. Modern readers, however, may not be ready for the details of that world. Aphrodite includes, in varying degrees of detail: deflowering, genital shaving, rape, threesomes, sex toys, sex with an eleven-year-old temple prostitute (entirely willingly on her part), Qabbalic fortune telling, induced abortion, tiny penis jokes, an orgy which begins with food and ends with a woman having sex with three or more men at once, a woman masturbating in public, a crucifixion, and a thirteen-year-old Cleopatra describing her orgasms and imprisoning her lover so that she can be sure he will not cheat on her.

Aphrodite has a certain historical significance. Louÿs also wrote Song of Bilitis (original: Chansons de Bilitis, 1894), a “long fanciful poem that pretended to be a translation of a lost classical document. It describes, in part, the love and ‘marriage’ between two women.”1 Between Songs of Bilitis and Aphrodite, Louÿs was one of the most prominent writers of lesbian literature of his time. He wrote for men and the male gaze,2 but lesbians at the time had few texts that they could claim as their own, and seized on Louÿs’ work. Louÿs “had a tremendous influence on modernist lesbian identity. His work, and its decadent fascination with the classical lesbian figure, influenced both Renée Vivien and Natalie Clifford Barney profoundly."3 Vivien (1877-1909) was a British poet who wrote in French and who was a high-profile out lesbian in Belle Époque Paris; “we might consider Vivien the first poet of the fully articulated modern lesbian identity.”4 Barney (1876-1972) was Vivien’s lover, the hostess of a celebrated Paris salon, and in general the doyenne of “the lesbian community referred to as ‘Paris-Lesbos’ until her death in 1972 at age ninety-six.”5 Barney was also Louÿs’ “most stable and most constant female friend–perhaps the only true one.”6 Louÿs was personally encouraging to the lesbians he knew, and Songs of Bilitis and Aphrodite provided literary-minded lesbians of the turn of the century with role models and attitudes they could aspire to.

Aphrodite is both well-written and spicy, and deserves better than the scorn many literary critics treat it with.

Recommended Edition

Print: Pierre Louÿs, Aphrodite; The Songs of Bilitis: Two Erotic Tales From the Fin de Siêcle. Louisville, KY: Chicago Spectrum Press, 2007.

Online: http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/aph/index.htm

1 Meredith Miller, Historical Dictionary of Lesbian Literature (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006). 113.

2 Briefly: in the great majority of visual media–and this is as true in 2019 as it was in 1975, when the following was written--“pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly.” Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16.3 (1975): 12. In speaking of written pornography, which Aphrodite is, the notion of whose gaze the text is written for is an important one. Louÿs wrote Aphrodite–and Songs of Bilitis–for himself and for his male friends–he had few female friends.

3 Miller, Historical Dictionary of Lesbian Literature, 113.

4 Miller, Historical Dictionary of Lesbian Literature, 151.

5 Tama Lea Engelking, “Translating the Lesbian Writer: Pierre Louÿs, Natalie Barney, and ‘Girls of the Future Society,’” South Central Review 22.3 (Fall, 2005): 63.

6 Jean-Paul Goujon, Pierre Louÿs: Une vie secrete, 1870-1925 (Paris: Fayard, 2002), 256, qtd. in Engelking, “Translating the Lesbian Writer,” 63.