The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana

by Jess Nevins

Salammbô (1862)

copyright © Jess Nevins 2022

Salammbô was written by Gustave Flaubert. Flaubert (1821-1880) is one of the major writers of the nineteenth century. Although he is best-known for Madame Bovary he has a respectable body of work, from short stories to dramas. His work is generally placed in the realist genre, but his skill as a stylist and technician is far above most of the other realists. Salammbô is one of the two or three greatest historical romances of the nineteenth century.

Salammbô is the story of Carthage in 237 B.C.E, during the mercenary rebellion described by the Greek historian Polybius in his Histories. The novel is not really about Salammbô, who is the priestess of Tanit, the moon, and is the daughter of the mighty general Hamilcar Barca. Salammbô is about the mercenary rebellion itself. Salammbô only appears as a subplot, albeit a compelling one and one which Flaubert himself saw as important to the novel. The mercenaries rebel against Carthage because the city elders refuse to give them their pay. The mercenaries are led by Mathô, a Libyan, and are opposed by first the Carthaginians and then by Hamilcar Barca himself. The war is lengthy, and there is a great deal of suffering and cruelty on and from both sides. The mercenaries win several temporary victories, only to suffer reversals. The mercenaries eventually lay siege to Carthage and destroy the city’s aqueduct, which subjects the city to thirst as well as famine. But the Carthaginians sacrifice children to their god Moloch, which brings rains to the city. Eventually Hamilcar Barca defeats the mercenaries, trapping most of their troops in a ravine in the mountains. Mathô is captured and forced to run a gauntlet through the city before he dies.

Salammbô is not central to the result of the rebellion, but she is influential on Mathô, who is desperately in love with her. Early in the siege Mathô breaks into Carthage to see Salammbô, but on the advice of his wily slave Spendius Mathô changes his mind and steals the zaïmph, the sacred veil of Tanit. The zaïmph is not to be touched by any mortal, and by stealing it Mathô hopes to destroy the morale of the Carthaginians. Soon afterward Mathô and Salammbô have a brief meeting. Mathô tells Salammbô his feelings for her and reveals that he stole the zaïmph. Infuriated, she calls down curses and imprecations on him for defiling the zaïmph. Mathô flees from her and escapes from the city. When the Carthaginians discover that the zaïmph has been stolen, their spirits are lowered, as Mathô planned. Eventually Salammbô steals into the rebels’ camp and goes to Mathô’s tent. He repeats his love for her and she submits to him. When he has fallen asleep she takes the zaïmph and returns with it to Carthage, thus rallying the Carthaginians. At the end of the novel, when Mathô runs the gauntlet, he falls dead at her feet. Remembering his words to her, she feels something for him, but then drops dead “for having touched the Veil of Tanit.”1

Salammbô has a lot in common, at least on a surface level, with Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Like Hugo, Flaubert created a fictional world with a truly astonishing amount of detail. Flaubert spent over four years researching Carthage, and Salammbô is proof of his efforts.2 There is a wealth of architectural, military, and social detail on every page. Like Hugo, Flaubert makes his chosen subject come alive on the page. But Salammbô is a far more compelling read than The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Flaubert’s declamatory, faux-epic style is smoother and more polished than Hugo’s more conversational tone. Hugo’s characterization is rather heavy-handed, while Flaubert’s characterization, such as it is–Salammbô is not a novel of characterization, but of history-in-action–is, if not subtle, then less overt and clumsy. Flaubert’s style has impressionismus, the quality in art of evoking emotions and impressions in the eyes and minds of the readers. And Flaubert has the advantage of describing romantic history, rather than gritty urban history.

There is, as mentioned, an enormous amount of historical detail in Salammbô. More than that, however, Flaubert devotes a great deal of space to describing, in detail, the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and physical feelings. Flaubert’s effort to create sensual impressions in the minds of the readers, to make the smells and sounds waft from the page, is not wasted; Salammbô is peculiarly vivid and atmospheric and sensual, and although the novel is ultimately exotic and alien to modern readers it is absorbing and feels real.

Flaubert described Salammbô as “locked into a set idea. She is a maniac.”3 She is obsessed with Tanit, the moon, and spends much of her time just looking at the stars and the moon. Salammbô is appalled when the zaïmph is stolen. But like Flaubert’s Emma Salammbô is disillusioned when she at last touches the sacred veil. Salammbô is really just a young woman filled with inchoate urges and longings. She is chaste but curious, decadent in the way she revels in her clothes and makeup but ignorant of lust, and innocently oblivious to the reality of the war outside Carthage. It is Mathô’s words which really touch her, but she remains an innocent to the end, wise in the ways of the gods but naive about humanity.

Salammbô has traditionally been seen as perhaps Flaubert’s most problematic work. But modern readers are not likely to find many of these criticisms particularly credible or relevant. Critics have found it “obscure” and “opaque,”4 criticisms far more subjective than objective and reflective more of the critic than the work itself. “It has been simultaneously accused of being both too modern (psychologically) and too distant (historically)…Salammbô has even been denounced as sounding the death-knell of the historical novel.”5 Modern readers may grant some quantum of credence to these views, but as an immersive reading experience Salammbô has few equals, and the open-minded reader will appreciate this.

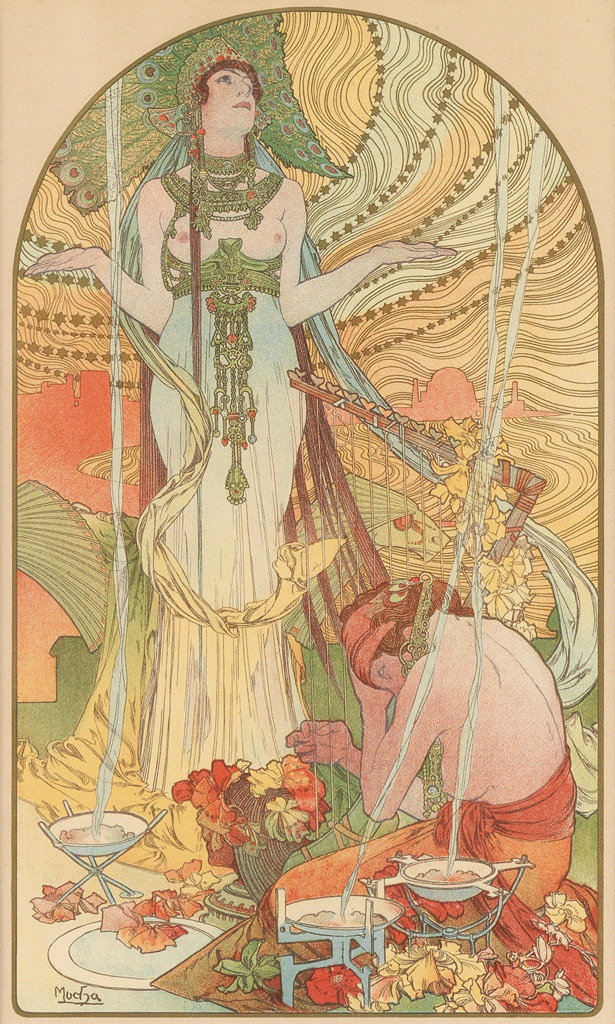

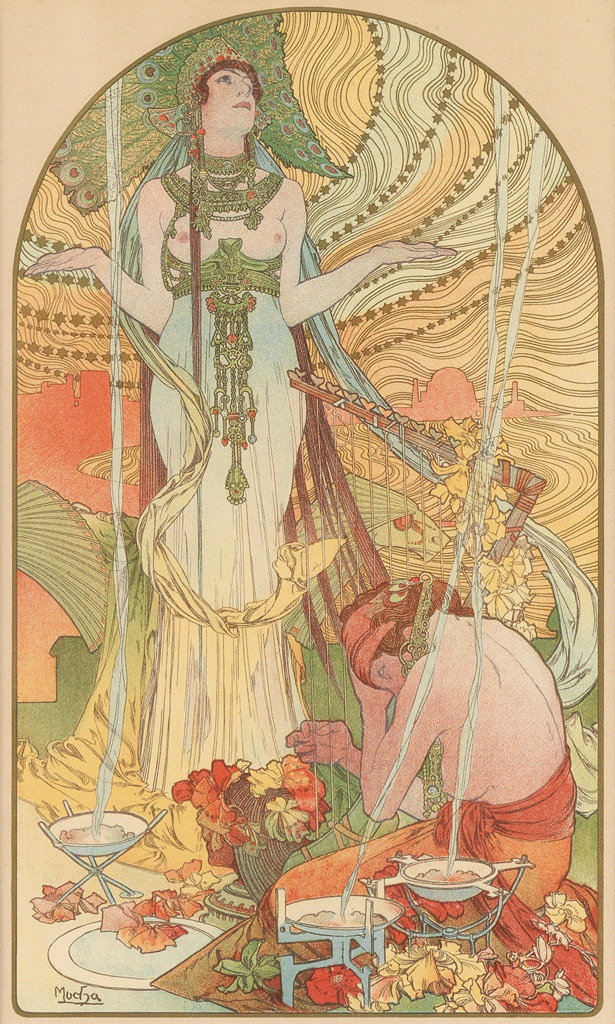

Lastly, like Lewis Wallace’s Ben-Hur, several nineteenth century editions of Salammbô are gorgeously illustrated in ways that modern editions of the novel are not.

Recommended Edition

Print: Gustave Flaubert, Salammbô. New York: Penguin, 1977.

Online: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001795512

For Further Research

Ellen O’Gorman, “Decadence and Historical Understanding in Flaubert’s ‘Salammbô,’” New Literary History 35, no. 4 (Autumn, 2004): 607-619.

1 Gustave Flaubert, Salammbô, transl. M. French Sheldon (London: Saxon & Co, 1886), 421.

2 Amusingly, the chief conservationist of the Department of Antiquities in the Louvre, an archaeologist named Guillaume Froehner, wrote an article listing all the details which Flaubert had supposedly gotten wrong, leading to a sharp, point-by-point rebuttal by Flaubert which shut up and shut down Froehner and the anti-Flaubertistes. Myra Jehlen, Five Fictions in Search of Truth (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), 14-15.

3 Qtd. in Kathryn Oliver Mills, Formal Revolution in the Work of Baudelaire and Flaubert (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2012), 114.

4 Anne Mullen Hohl, “Salammbô,” in Laurence M. Porter, ed., A Gustave Flaubert Encyclopedia (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 283.

5 Hohl, “Salammbô,” 283-284.