The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana

by Jess Nevins

"The Spider of Guyana" (1860)

copyright © Jess Nevins 2022

“The Spider of Guyana” (original: “L’Araignée Crabe”) was written by “Erckmann-Chatrian” and first appeared in Contes Fantastiques (1860). Émile Erckmann (1822-1899) and Alexandre Chatrian (1826-1890) were French journalists who became famous in their lifetime and are still best-known for their accounts, fictional and non-fictional, of life in the French countryside.

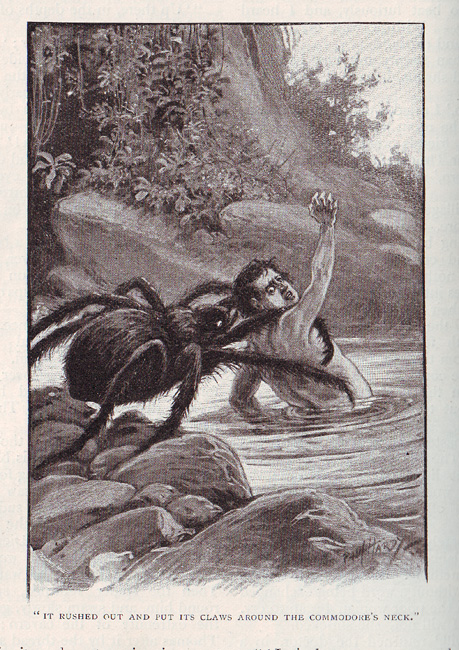

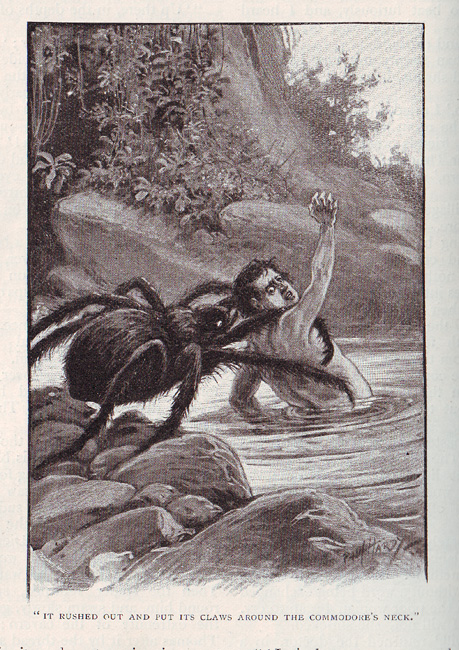

“The Spider of Guyana” is about the resort town of Spinbronn in the mountains of Germany. The story describes why the town is no longer used as a resort. The waters at Spinbronn were prescribed for sufferers of gout, and Spinbronn was a popular resort, especially for Doctor Daniel Haselnoss and his patients. One of these patients is Sir Thomas Hawerbrook, a stout Englishman and the favorite of Mr. Bremen, the story's narrator. Unfortunately, one day bodies start to emerge from the cavern which is the source of the waters of Spinbronn. The cavern is covered with moss, ivy, and shrubs and has not been plumbed, so the bodies of birds which fell from the waters are unexplained but ignored. But a human skeleton emerges, quickly followed by “a veritable ossuary...skeletons of animals of all sorts, quadrupeds, birds, reptiles. In fact, all the most horrible things that could be imagined.”1 A local doctor, Christian Weber, had spent time in St. Domingo (Haiti) before and during the revolution there and returned to the Pirmasens with Agatha, “an old negress...a very ugly old woman.”2 Sir Hawerbrook and Doctor Weber get along just fine, but they disagree sharply over Doctor Weber’s most recent specimen, the spider of Guyana:

“’There...is the most hideous work of the Creator. I tremble only to look at it.’”

“And, sure enough, a sudden pallor spread over his face.”

“’Bah! That is all childish nonsense. You hear your nurse scream at a spider, you were frightened, and the impression has remained. But if you regard the creature with a strong microscope, you would be astonished by the delicacy of its organs, at their admirable arrangements, and even at their beauty.’”3

Sir Hawerbrook and Mr. Bremen decide to climb up to the cavern from which the waters of the Spinbronn fall, and Sir Hawerbrook takes a swim in the lake outside the cavern. When Bremen returns from strawberry picking, Hawerbrook is gone. Bremen sees a dark object moving in the cavern and flees, panicked. He runs to Doctor Weber, who uses hypnosis on Agatha to force her to use her Second Sight to divulge what happened to Sir Hawerbrook. She says that a giant spider of Guyana got him. So Doctor Weber organizes a lynch mob, and they smoke the spider out of its cavern and burn it to death.

“The Spider of Guyana” is not outright frightening, but it is an entertaining Big Bug story, done with a straightforward seriousness that later, campier Big Bug stories are unable to assume. Erckmann and Chatrian were later praised by the likes of M.R. James and H.P. Lovecraft, but although the tale is told neatly and cleanly the story is not otherwise impressive. It is entertaining, but as a horror story it lacks the ability to cause fear in the modern reader. The story is also marred by the racist characterization of Agatha.

“The Spider of Guyana” is an interesting divergence from traditional monster stories, both Big Bug and regular-sized:

This masochistic dimension of monster stories is already contained in Frankenstein and in the Christian and pagan traditions. Monsters, according to this logic, frequently come to take revenge on deserving individuals and even cultures. God or fate dispatches terrible creatures to dispense the wages of sin. Human arrogance is repaid by chaos and destruction.4

Certainly the majority of the Big Bug narratives, which appeared not in the pulps of the 1920s and 1930s but rather in the science fiction B movies of the 1950s, were interpreted in this fashion:

Critics and historians have invariably interpreted these cinematic big bugs as symbolic manifestations of Cold War era anxieties, including nuclear fear, concern over communist infiltration, ambivalence about science and technocratic authority, and repressed Freudian impulses…Hollywood's mammoth arthropods should be taken more literally, less as metaphors than as insects, and that the big bug genre should be analyzed in the context of actual fears of insect invasion and growing misgivings about the safety and effectiveness of modern insecticides in 1950s and early 1960s America. In movies like Them!, worries about real-life insects on the loose, notably gypsy moths and imported fire ants, and uneasiness about pesticides like DDT were refracted through a cultural lens colored by superpower rivalries, nuclear proliferation, and a wide range of social tensions.5

But “The Spider of Guyana” does not fit into this schemata. In the story the Spider is simply a natural event, unattached to and unreflective of human actions and desires. In this sense, “The Spider of Guyana” can be seen as a forerunner to much twentieth century horror fiction, in which the monsters or haunted houses or curses happen not because of what humans do, but because the universe itself is uncaring or inimical. H.P. Lovecraft, in his “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” singles out Erckmann-Chatrian for praise, and says of “The Spider of Guyana” that it is “full of engulfing darkness and mystery [despite] embodying the familiar overgrown-spider theme so frequently employed by weird fictionalists.”6 The relative moral emptiness of “The Spider of Guyana” is resonant in certain respects with the amoral cosmic horror of Lovecraft’s fiction, and it can be speculated how much of an effect Erckmann-Chatrian had on the development of Lovecraft’s horror fiction.

Recommended Edition

Print: Erckmann-Chatrian, The Invisible Eye. Ashcroft, BC: Ash-Tree Press, 2012.

1 Erckmann-Chatrian, “The Spider of Guyana,” in The Man-Wolf And Other Tales (Expanded Edition) (Rockville, MD: Wildside Press, 2009), 180.

2 Erckmann-Chatrian, “The Spider of Guyana,” 180-181.

3 Erckmann-Chatrian, “The Spider of Guyana,” 182.

4 Stephen T. Asma, On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 209.

5 William M. Tsutsui, “Looking Straight At Them! Understanding the Big Bug Movies of the 1950s,” Environmental History 12 (April 2007): 237.

6 Lovecraft, “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” 184.