The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana

by Jess Nevins

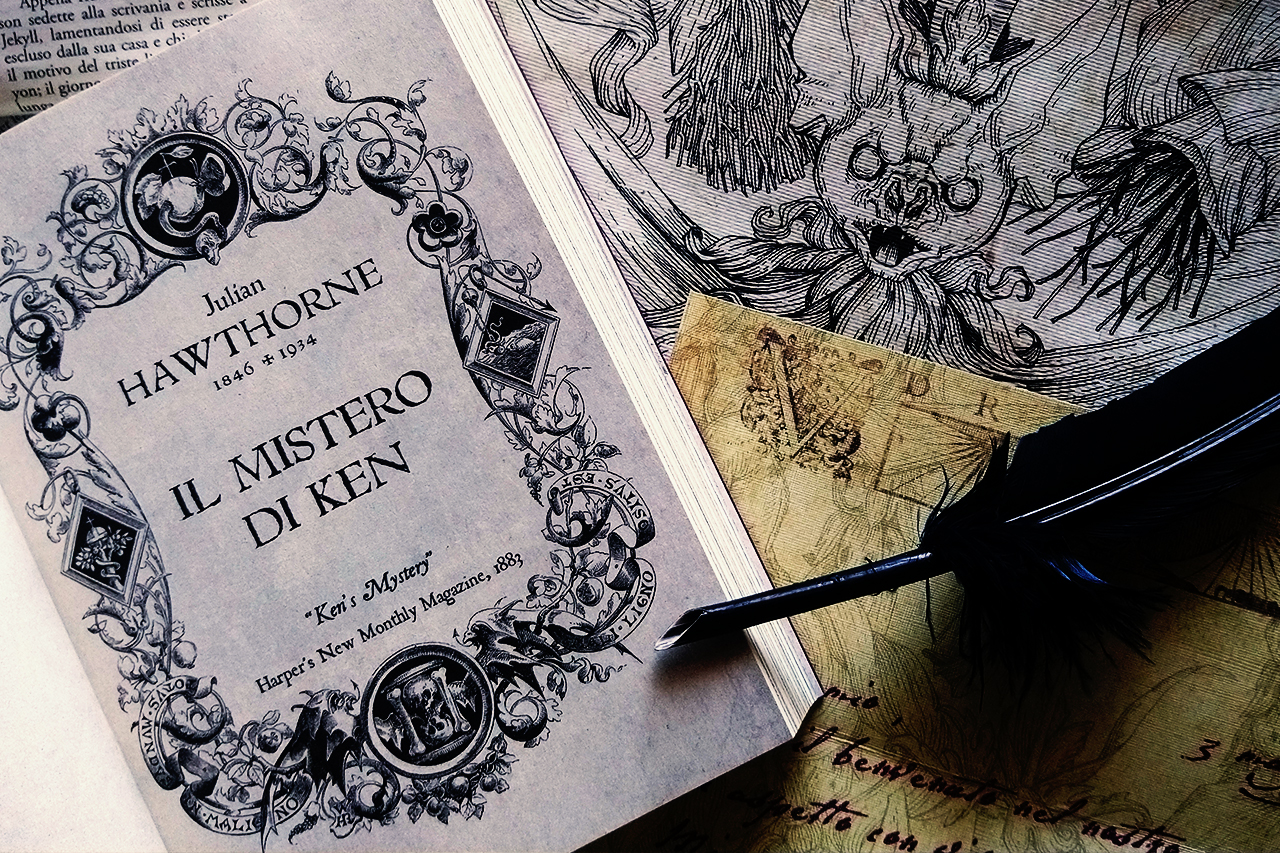

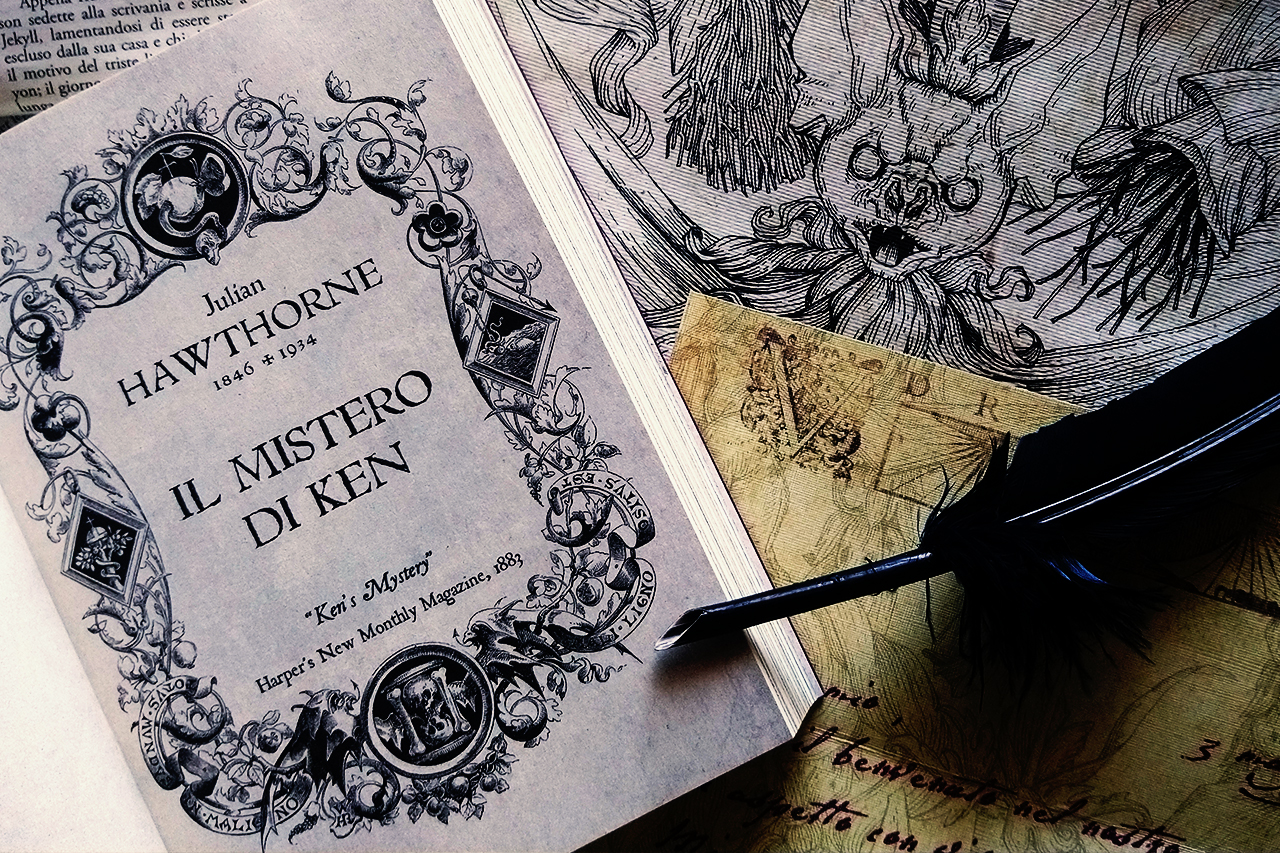

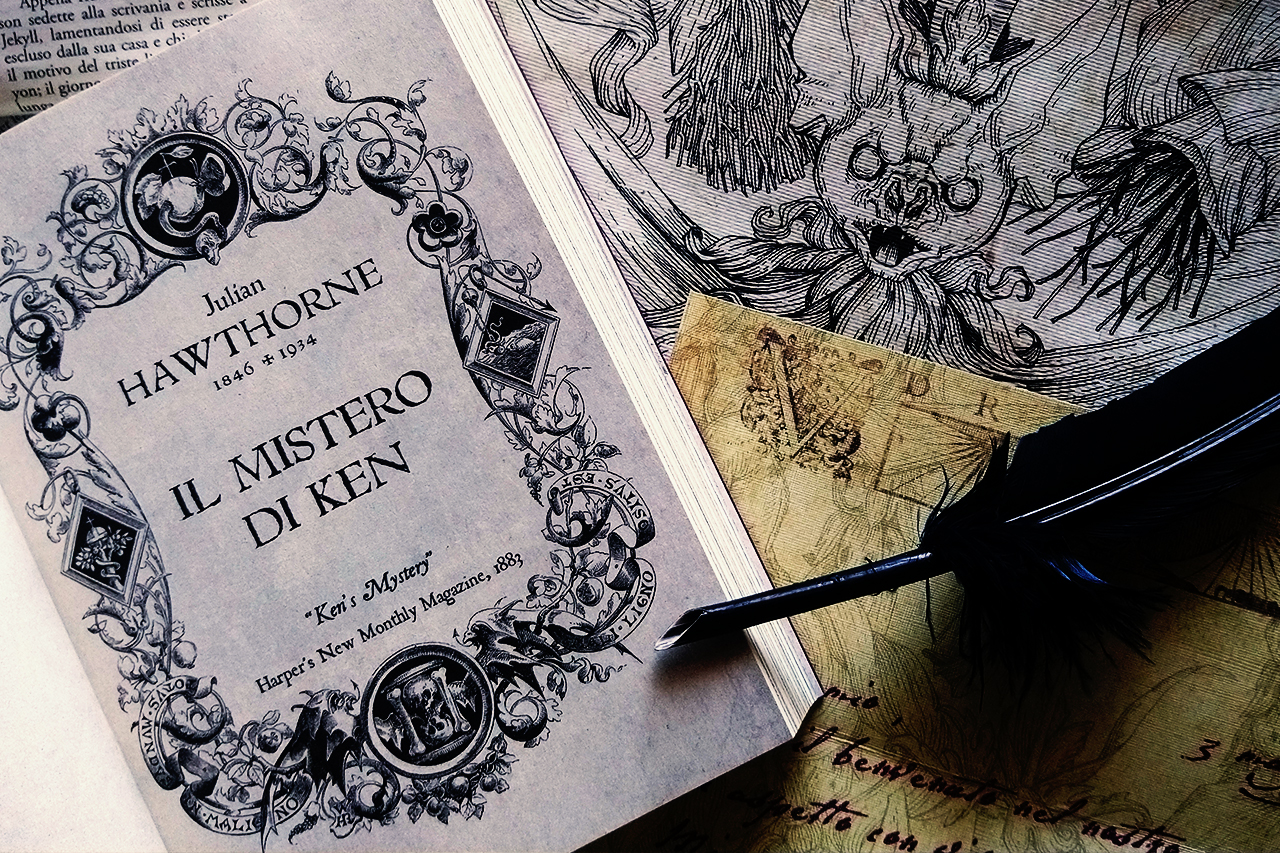

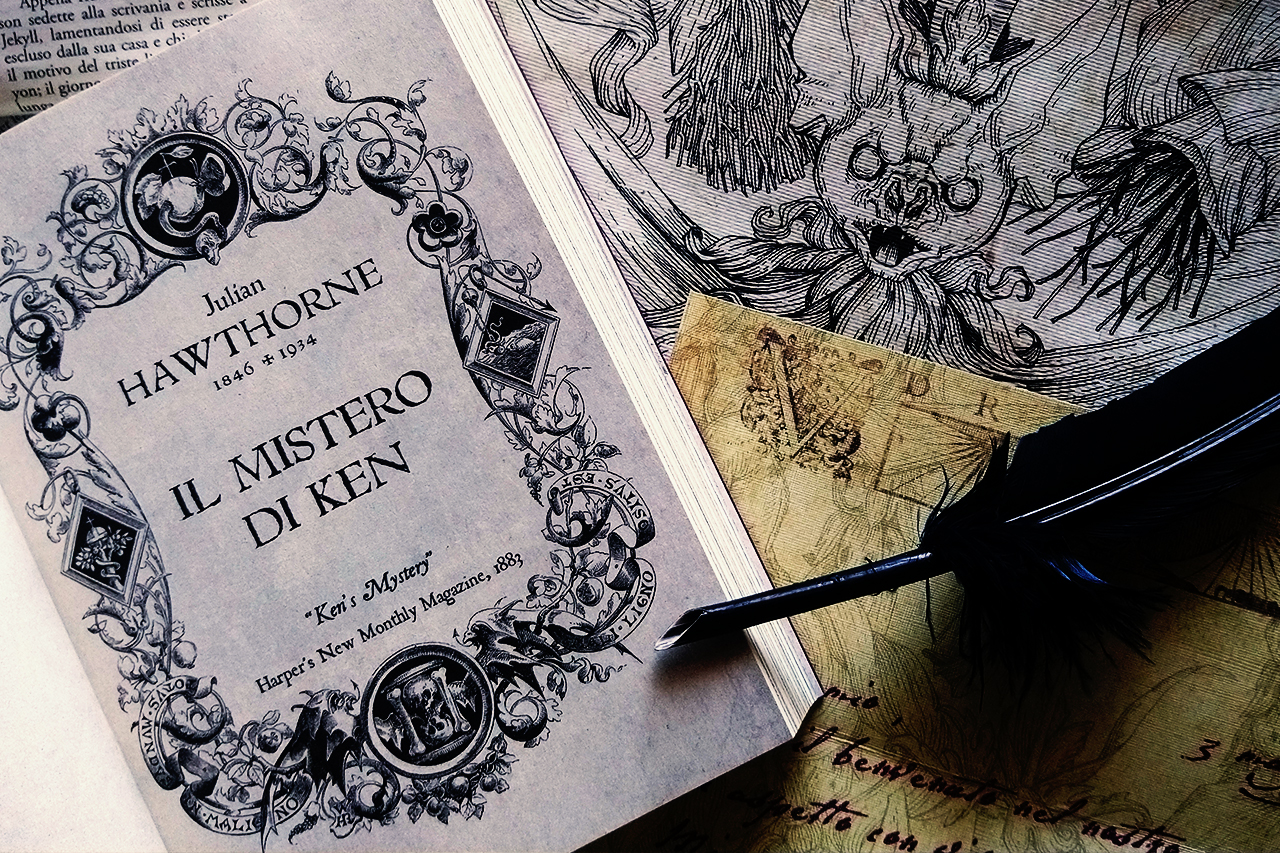

"Ken's Mystery" (1883)

copyright © Jess Nevins 2022

“Ken’s Mystery” was written by Julian Hawthorne and first appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 67, no. 402 (Nov 1883). Hawthorne (1846-1934) was the son of Nathaniel Hawthorne, and a journalist and writer of a wide range of material from occult stories to critical work to novels about Thomas Byrnes. “Ken’s Mystery” is a pre-Dracula vampire story, and is interestingly different from most of the other vampire stories which appeared before Stoker.

“Ken’s Mystery” is about the narrator’s friend Keningale, or “Ken,” an upper-class American who went to Europe to study abroad and came back graver, broodier, and not at all the lighthearted man about town that he had left as. The narrator, an old friend of Ken, decides to visit Ken and share a pipe and a cup with him. In Ken’s lodgings he finds several sketches of a striking woman, and the banjo which the narrator had given Ken before he left. The banjo, however, is unaccountably aged, looking as if it were two centuries’ old rather than two years. The narrator is puzzled by this, and Ken, troubled by his memories and the date–it is Halloween–opens up about his experience.

Ken had visited Ireland, and gone to a remote, decrepit town in County Cork on the coast. He was delighted with the beautiful landscape, and he struck up a friendship with some of the soldiers in the fort overlooking the town. One night one of the soldiers warned him to “mind your eye, now, going back, my dear boy...’tis a spooky place, that graveyard, and you’ll likely as meet the black woman there as anywhere else.”1 Some time later, at Ken’s farewell dinner, the fort’s surgeon, a man with a wealth of folklore at his command, tells Ken the story behind one particular house in town. Many years before Ethelind Fionguala (“which being interpreted signified ‘the white shouldered’”2) had been stolen away on her wedding night by a band of vampires. Before she could be consumed, however, a local man happened upon the band and shot them, and then brought Ethelind to his house. Ken enjoys the story but does not have the chance to pursue it. When he leaves the dinner, Ken is drunk, and he quickly finds himself walking on a path he does not recognize, among an unfamiliar landscape. He hears female laughter behind him but sees no one. Eventually he finds himself approaching a graveyard, and sees, leaning on one of the gravestones, a woman wearing a long, hooded cloak.

They strike up a conversation, she flirtatious and teasing and he curious and responsive. She calls herself “Elsie” and asks him to play something on his banjo for her, and she does. She warns him when he is about to step into a deep ravine, but when he turns to thank her she has vanished. He continues on his way and is soon in the town, and, wanting to see her again, goes to the house where Ethelind used to live. He stands outside a window and plays a slow love song, and she appears in the window and throws him a key. He goes inside, and she leads him through the darkened house into a lushly furnished room which is, however, unlit by any fire and quite cold. There is a dinner laid out for him, and she invites him to eat, but she won’t: “You are the only nourishment I want. This wine is thin and cold. Give me wine as red as your blood and as warm, and I will drain a goblet to the dregs.”3 She is cold, physically, her lips especially so, but he is taken with her, and they continue their flirtation. She tells him that the ring on her finger “is the ring you gave me when you loved me first. It is the ring of the Kern–the fairy ring, and I am your Ethelind–Ethelind Fionguala.”4 He only says, “So be it.” He stays in the room and plays for her, and as he grows colder she becomes increasingly bright and lively. He passes out on her shoulder, and awakens in the ruins of a house:

“Well, that is all I have to tell. My health was seriously impaired; all the blood seemed to have drawn out of my veins; I was pale and haggard, and the chill–ah, that chill,” murmured Keningale, drawing near to the fire, and spreading out his hands to catch the warmth–“I shall never get over it; I shall carry it to my grave.”5

“Ken’s Mystery” is generally seen as Hawthorne’s best short story. It feels more Edwardian than Victorian, having a sleek, clean narrative style, complete with light badinage between the narrator and Ken, and a wealthy American protagonist touring Europe, all of which are attributes of stories in the slick magazines of the Edwardian years. In that respect “Ken’s Mystery” is ahead of its time; one would never guess that this story was written before Mrs. Molesworth’s “The Story of the Rippling Train,” “Ken’s Mystery” does not add much to vampire lore: the figure of Ethelind represents no advance on previous vampires, she is a typical late Victorian Fatal Woman, and the story does not contribute anything to the iconography or folklore of the vampire. But Julian Hawthorne and Bram Stoker were best friends, and it is possible that Stoker read “Ken’s Mystery” and that Dracula was influenced by it. The folklore of the two stories are different, but the erotic element of the female vampires in Dracula has some similarity to the erotic feel and the mounting anticipation of seduction–her by him and him by her–at the end of “Ken’s Mystery.” In the 1880s vampirism was popular in French Decadent literature because of this sexuality,6 but “Ken’s Mystery” has nothing of either the French tradition of vampire stories or of Decadence in it being, if anything, closer to a modernized recapitulation of traditional Irish myth.

“Ken’s Mystery” is fine vampiric entertainment.

Recommended Edition

Print: Julian Hawthorne, The Rose of Death and Other Delusions. Ashcroft, BC: Ash-Tree Press, 2012.

Online: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100586417

1 Julian Hawthorne, “Ken’s Mystery,” in David Poindexter’s Disappearance: And Other Tales (New York: D. Appleton, 1888), 68.

2 Hawthorne, “Ken’s Mystery,” 70.

3 Hawthorne, “Ken’s Mystery,” 90.

4 Hawthorne, “Ken’s Mystery,” 91.

5 Hawthorne, “Ken’s Mystery,” 93.

6 Brian J. Frost, The Monster with a Thousand Faces: Guises of the Vampire in Myth and Literature (Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1989), 46.